ILYA EHRENBURG**ONS DAGELIJKSCH BROOD**WERELDBIBLIOTHEEK

Kenmerken

- Conditie

- Gebruikt

- Levering

- Niet van toepassing

Omschrijving

ILYA EHRENBURG

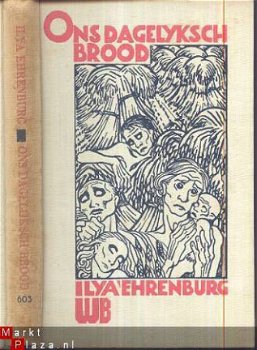

**ONS DAGELIJKSCH BROOD**

KRONIEK VAN HET HEDEN

VERTALING UIT HET RUSSISCH VAN

ELSE BUKOWSKA

BANDONTWERP R. HUYSMANS-KOOYMAN.

1933

WERELDBIBLIOTHEEK AMSTERDAM-SLOTERDIJK.

ARTIKEL INVENTARIS CODE 8.380

FORMAAT 188 X 123 X 18 + 143 PGS + 320 GRS.

VERZENDING IN BELGIE 2,35 EURO NR EUROPA 7,35 EURO

.WERELDBIBLIOTHEEK

The Soviet author Ilya Grigorievich Ehrenburg (1891-1967) is best known for his role as a man of letters throughout the first 50 years of Soviet history. He wrote more than 100 books and pamphlets, which range from lyric verse, to fiction, to journalism.

Ilya Ehrenburg was born on Jan. 27, 1891, in Kiev. He came from a middle-class Jewish family, and his father worked in a brewery. The rampant anti-Semitism of Kievan life at the turn of the century made a deep impression on young Ehrenburg. Throughout his life he engaged in the fight against racism. In 1896 Ehrenburg's family moved to Moscow, where Ilya entered the First Moscow Gymnasium. Although he was a poor student, he drew inspiration from Moscow life. Leo Tolstoy kept a townhouse next to the Ehrenburg home, and Maxim Gorky lived for a short while in the Ehrenburg house.

Ehrenburg's formal education ended in 1907, when he was expelled from the gymnasium for leading an anticzarist strike. He had been exposed at school to ideas of revolution and early leaned toward the Bolshevik ideology. Ehrenburg was arrested several times in 1907 and 1908 for radical writings, and he was finally exiled in 1908. His exile brought him to Paris in 1909, where he settled down in the emigre artists' colony.

The experiences of Ehrenburg in Paris from 1909 to 1917 and from 1924 to 1940 left an indelible impression on his life and art. His acquaintance with Pablo Picasso and Diego Rivera introduced him to the avant-garde in the arts. His contacts among Russian emigres led him to reflect on the problems of Russia's historical destiny in the context of European civilization. During the 1910s Ehrenburg led the life of a literary bohemian, attending lectures at the Haute École des Études Sociales, working as a tourist guide and stevedore, and testing his talent as a writer. His first literary work was poetry, and he published a book of poems entitled Parisat his own expense in 1910. Ehrenburg spent much of World War I working as a correspondent for various Russian newspapers.

Ehrenburg had deep reservations about the Russian Revolution. He returned to Russia in 1917 after the February Revolution, working at various literary and journalistic jobs until 1921. Ehrenburg married in 1919, and he and his family left the Soviet Union in 1921, traveling about Europe until 1924, when they settled in Paris. In 1921 in Belgium, Ehrenburg wrote his most successful novel, The Extraordinary Adventures of Julio Jurenito and His Disciples. This satirical novel portrays the comical adventures of a Mexican as he confronts the absurdities of capitalist and socialist life in Europe and the Soviet Union.

From 1924 until his return to Moscow in 1940, Ehrenburg lived the life of a journalist and free-lance writer throughout Europe. Although he came to accept the role of the Soviet Union in world affairs and to praise the Soviet Union's opposition to fascism, Ehrenburg was hesitant about committing himself to life in the Soviet Union. In 1932 he became a regular correspondent for the Soviet newspaper Izvestia. His duties as journalist took him to Spain in the 1930s, where he wrote about the Spanish Civil War. In 1940 he was again in Paris, then occupied by German troops. His book The Fall of Paris (1942) presents an excellent account of the Occupation.

Ehrenburg returned to Moscow in 1940 with a worldwide reputation. He worked as a war correspondent for the Soviet newspaper Pravda throughout World War II. Ehrenburg's attitudes toward the unreasonable strictures placed on the Soviet writer by socialist realism were ambivalent until after the death of Stalin. In 1954, however, Ehrenburg published The Thaw, depicting the harm done to Soviet writing by the heavy hand of the Soviet bureaucracy. The title of this novel became the name of the liberal decade of the 1950s in Soviet literature. Ehrenburg further contributed to the thaw in Soviet literary policy with his memoirs, People, Years, Life, published in the late 1950s and early 1960s. Ehrenburg's memoirs are a valuable source of information for students of Soviet literature.

Ehrenburg was an urbane man, an extremely prolific writer, and a protector of the arts. He died in Moscow on Sept. 1, 1967.